Dealing with Apparently Problematic and Conflicting Ḥadīth

Mufti Muntasir Zaman

Site admin note: This article was originally published on Mufti Muntasir Zaman's personal website, ahadithnotes.com, although it was abruptly removed for some unknown reason. I thus endeavoured to create a copy of it here before it disappeared from Google's cache and was lost for good.

﷽

The example of the intellect is sight

free of defects and illnesses, and the example of the Qurʾān is the sun

with rays spread out. Hence, the seeker of guidance that dispenses with

one of them in lieu of the other is most fit to be included among fools.

The one who turns away from the intellect, sufficing himself with the

light of the Qurʾān is like one exposed to the light of the sun while

closing his eyelids; there is no difference between him and the blind.

Thus, the intellect with revelation is light upon light. The onlooker

with an eye blind to one of them specifically is drawn in by a deceptive

rope.[1]

– Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī (d. 505 AH)

The surge of criticisms in recent times towards supposedly problematic

ḥadīths generally rest on the claim that such ḥadīths are absurd,

unscientific, impossible, or contradictory. Every ḥadīth whose content

is seen as problematic will have a specific explanation, for which

relevant literature can be consulted. This article will highlight broad

guidelines that are to be kept in mind when dealing with narrations of

this nature. After some preliminary thoughts, four points will be

proffered for consideration: (1) the limits of human reason and

experience; (2) the importance of contextualization; (3) the usage of

figurative speech; and (4) the need to distinguish between impossibility

and unlikelihood. In no way are these guidelines meant to be

exhaustive. As a first response, they can help to assuage the concerns

of a Muslim whose conscience is constantly agitated by reading

apparently problematic ḥadīths. Detailed discussions on specific ḥadīths

can be offered on a case by case basis.

In numerous places in the Qurʾān, Allah calls upon humankind to use their intellect and to contemplate the perfection of His creation. He says, “And now We have sent down to you [people] a Scripture to remind you. Will you not use your reason?”[2] In other verses, He reprimands those who do not use their intellect; “But the disbelievers invent lies about Allah. Most of them do not use reason”[3] is a striking case in point.[4] That the Qurʾān transcends a mere exposition of raw assertion by engaging in a process of argumentation and dialogue—it is the “evincive proof” (burhān) and “conclusive argument” (al-ḥujjah al-bālighah)—is indicative of its appeal to the human mind.[5] Therefore, there exists no incongruity between reason and revelation; the former in fact leads one to appreciate the latter while the latter enjoins and exemplifies the former.[6] There is, however, an important caveat that should not escape our attention: the reasoning has to be sound and the revelation authentic.[7]

From the formative period of Islamic history, scholars have written books to address apparently contradictory ḥadīths, a field known as mukhtalif al-ḥadīth,[8] and ḥadīths that apparently conflict with other evidences or external reality, a field known as mushkil al-ḥadīth.[9] In this vein, Imām al-Shāfiʿī (d. 204 AH) authored Ikhtilāf al-Ḥadīth,[10] regarded as one of the earliest works on the subject. Analogous works include Ibn Qutaybah al-Dīnawarī’s (d. 276 AH) pioneering monograph, Taʾwīl Mukhtalif al-Ḥadīth, Abū Jaʿfar al-Ṭaḥāwī’s (d. 321 AH) peerless compendium, Sharḥ Mushkil al-Āthār,[11] and Abū Bakr Ibn Fūrak’s (d. 406 AH) masterpiece, Mushkil al-Ḥadīth wa Bayānuhū. Scholars also dealt with such narrations in their general Ḥadīth commentaries when the occasion arose. Abū Bakr Ibn Khuzaymah (d. 311 AH) confidently proclaims, “I am unaware of any two authentic narrations of the Prophet that are contradictory. If anyone comes across such narrations, let him bring them to me so that I can reconcile them.”[12]

It goes without saying that before venturing to clarify any misunderstanding or problematic content in a ḥadīth, it is paramount to ensure its authenticity. A person should not expend energy in trying to reconcile, say, a fabricated ḥadīth with external realities, because it cannot be reliably attributed to the Prophet to begin with, and therefore, should not be a matter of concern. [13] It is pointless to explain the fabricated ḥadīth, for instance, that states, “Hornets were created from the heads of horses and bees from the heads of cows” because this supposed ḥadīth is baseless. [14] Mullā ʿAlī al-Qārī (d. 1014 AH) reminds his reader of the ancient adage: first stabilize the throne firmly, then worry about engraving it (thabbit al-ʿarsh thumm unqush), that is, before concerning ourselves with whether the meaning is correct, we should ensure whether the report is even reliable to begin with.[15] In his magnum opus, al-Ṭaḥāwī’s modus operandi was to examine only acceptable narrations.[16]

A ḥadīth is often transmitted via multiple routes (riwāyāt), which may differ in wording. When attempting to understand a ḥadīth, the need to examine it in view of all its routes of transmission in order to acquire a holistic understanding of it cannot be stressed enough. Until all the routes of a ḥadīth are collected and analyzed as a whole, Ibn al-Madīnī explains, its errors will not become apparent.[17] Take the Prophetic ḥadīth narrated via ʿĀʾishah and Buraydah that a human body has 360 joints and a person is required to perform a virtuous deed for each joint.[18] In two variant routes of transmission from Abū Hurayrah and Ibn ‘Abbās, this ḥadīth is narrated with the words “360 bones,” which is incongruent with modern knowledge of human anatomy.[19] But these routes are defective. The route of Ibn ‘Abbās contains the impugned narrator al-Layth ibn Abī Sulaym while the route of Abū Hurayrah suffers from several flaws, viz. disagreement among, and contentions regarding, the sub-transmitters, isolation in transmission, and conflict with more authentic routes. Although there are multiple routes for the ḥadīth, the correct version contains the words “360 joints.”[20]

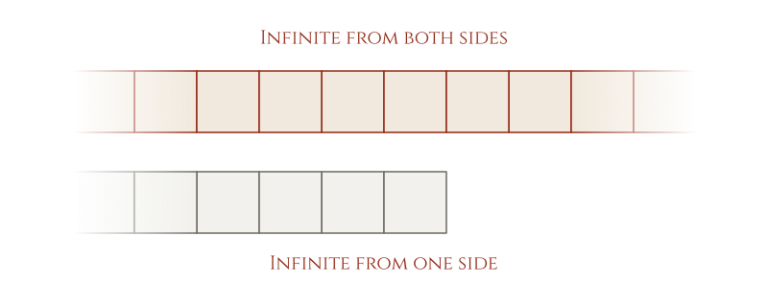

The main focus here is how to deal with problematic ḥadīths (mushkil al-ḥadīth). Before proceeding, however, a word on conflicting ḥadīths (mukhtilaf al-ḥadīth) is in order. Jurists laid out the following procedure for dealing with conflicting ḥadīths.[21] The first step is to harmonize (jamʿ) between the conflicting reports.[22] The Prophet prohibited a person from placing one leg on the other when lying down,[23] but he reportedly did exactly that on one occasion.[24] Al-Khaṭṭābi (d. 388 AH) explains that the prohibition pertains to the scenario where placing one leg on the other will expose one’s private part; the Prophet did so in a manner that ensured his lower body was concealed.[25] When harmonization is not possible, one is to seek out evidence of abrogation (naskh).[26] As we have seen elsewhere, the Prophet is reported to have both allowed and prohibited the writing of his ḥadīths.[27] To avoid any shortcomings in preserving the Qurʾān, the Prophet prohibited the Companions from writing ḥadīths. Once there remained no fear of such neglect, he allowed them to write material besides the Qurʾān.[28] In the absence of evidence to suggest abrogation, one should prefer (tarjīḥ) one ḥadīth over the other based on a list of factors related to the chain of transmission, the text, and other issues.[29]

Guidelines

When a Muslim believes the Prophet received information about the unseen, how could he reject something authentically attributed to him only because it seems far-fetched in light of the conventional understandings of the world? If a ḥadīth describes how Satan flees flatulating upon hearing the call to prayer,[30] how can a Muslim, who accepts that the Prophet receives information about the unseen, reject it under the pretext that it is absurd when it is describing something beyond the scope of his intellect and/or experience?

To understand this point better, note that there are three primary sources from which people acquire knowledge: sound senses, reason, and a truthful report.[31] The first source includes the five senses, i.e. hearing, seeing, smelling, tasting, and touching. We use these senses to perceive the world around us, within their limitations. Even the thought of using a particular sense beyond its limitation, e.g. to try to smell with one’s sense of touch, is foolish. The second source is human reason.[32] We come to know the texture of silk with our sense of touch and the smell of musk with our sense of smell, but none of these senses can help us to determine how they were prepared and what purpose they serve, simply because this is conceptual and propositional knowledge that lies beyond the senses and can only be comprehended by the intellect. This is where our reason comes in and guides us; but reason also has its limits.[33] The third source of knowledge is accurate information provided through truthful reporting, such as historical anecdotes or testimony. The most important form of such transmitted information for a believer is divine revelation, the scope of which extends beyond both human reason and experience. It would be unreasonable to reject information derived from divine revelation merely because it seems prima facie absurd. To say revelation transcends human reason is not to say it is irrational—it is, rather, supra-rational, in the sense that it transcends the (necessarily limited) cognitive competencies of human reason.[34] In other words, it is incorrect to weigh revelation solely on a scale as limited as human reason and experience.[35] One who attempts to do so, Ibn Khaldūn (d. 808 AH) observes, is like a person who wishes to weigh the mountains on a goldsmith’s weighing scale.[36]

Reports authentically related from the Prophet are best understood in their context. Failing to contextualize will lead a person to criticize a ḥadīth anachronistically. It would be unfair for a critic to object to a particular practice or statement of the Prophet only because it is considered unacceptable in the critic’s current social milieu. Modern critics are often guilty of imposing certain ideals onto their reading of history; what does not correspond to these ideals is to be unquestionably abandoned because it is “backward” or “irrational.” It is therefore disingenuous to criticize the marriage of our mother ʿĀʾishah at a young age based on modern marital ethics. Despite the lengths the Prophet’s most ardent critics went to criticize him, his marriage with ʿĀʾishah was never considered problematic for them since marriage at a young age was socially acceptable. It is only recently that this has become an issue. The first to formally appraise this aspect of the Prophet’s life negatively in the early 1900s was the Orientalist David Margoliouth (d. 1940).[37]

This is not to deny the universality of the Prophet’s example for humankind throughout time. The Prophet was undoubtedly sent “to bring good news and warning to all people.”[38] Legal theorists have formulated the maxim “al-ʿibrah bi ʿumūm al-lafẓ lā bi khuṣūṣ al-sabab (consideration is given to the generality of the wording and not to the specific cause)” when studying divine scripture. However, Ibn Daqīq al-ʿĪd (d. 702 AH) qualifies this maxim by cautioning students to be aware of the difference between “the indication of context and signs (qarāʾin) towards specifying the generality” and “the occurrence of a general rule in a specific scenario” because the mere occurrence of a generality in a scenario does not specify it.[39] In other words, this maxim is not to be taken as a universal rule. He further explains, “Context provides clarity on what is ambiguous, specifies what is ambivalent, and frames statements according to their intended purpose.”[40] In any case, studying the context of a ḥadīth to better understand its rationale and application is a far cry from dismissing ḥadīths arbitrarily on the pretext that they are outdated.[41]

At times a figurative reading of a ḥadīth can easily remove the difficulty in understanding its contents. To interpret the sayings of the Prophet without considering the tools of rhetoric can be misleading, especially when the use of figurative speech (majāz) is common in Arabic, as in other languages.[42] This equally applies to verses of the Qurʾān where a literal reading would convey an incorrect meaning.[43] Take the example of the ḥadīth, “Two months of ʿĪd never fall short: Ramadan and Dhū al-Ḥijjah,” which apparently means that these two months will never fall short of thirty days. Taken at face value, this contradicts reality. However, it is interpreted figuratively to mean that these two months will never fall short of spiritual value even though their days may be twenty-nine, which is a completely plausible explanation.[44]

Losing sight of the broader message of a ḥadīth by delving into its literal words can deter one from understanding its correct intent. When taken at face value, the ḥadīth where the Prophet tells Abū Dharr that “during sunset, the sun prostrates underneath the ʿArsh (Divine Throne) and then seeks permission to rise again” is difficult to reconcile with science. However, there is a greater message embedded in these words. The Prophet took this opportunity—when the world goes through a magnificent transformation, that of the alternation of night and day—to teach mankind that this marvelous phenomenon happens only with the permission of Allah. The ʿArsh encompasses the entire creation, and therefore, the sun is always beneath the ʿArsh.[45] This moving with Allah’s permission and by His command is described as its “prostration;” the prostration of each creation manifests according to its individual state of being, as Allah has stated in the Qurʿān.[46]

The Prophet articulated his comment according to what Abū Dharr observed in front of him. Expressing a specific orbital path or other material reality was not the purpose of the ḥadīth; misconstruing it as such would only serve to obscure the intended message.[47] It is inaccurate to study hadīths of this nature through a strictly materialistic and naturalistic lens because the Prophet’s mission was not to provide guidance on scientific matters.[48] Shāh Waliullāh (d. 1176 AH) makes the apt observation that the prophets would not occupy themselves with matters not relevant to “the refinement of the soul and governing of the community unless it was incidental.”[49] Even in daily conversations today, people use phrases that are unscientific if taken literally, e.g. at sunrise or sunset. A study of the Prophet’s ḥadīths demonstrates that they possessed a rhetorical consistency which can be dubbed a Prophetic style of speaking.[50] Scholars were well aware of this phenomenon. While grading a particular ḥadīth, Ibn ʿAdī (d. 365 AH) states, “It does not resemble the words of the Prophet”[51] and elsewhere al-Mundhirī (d. 656 AH) states, “But this ḥadīth gleams with a shine from the light of prophethood.”[52] One characteristic of the Prophetic style was hyperbole.[53] Hence, early Muslim scholars have not interpreted ḥadīths that state “he is not from among us” as excommunication from the faith.[54] To fully grasp the message of certain ḥadīths, therefore, one is required to be conversant with the language of Ḥadīth.

Finally, it is essential to make a distinction between what is fundamentally impossible (mustaḥīl) and what is merely unlikely (mustaghrab) though within the realm of what is possible. Impossibility is a quality intrinsic to a thing itself. Something impossible can never be; a circle can never take the shape of a square. On the other hand, deeming something unlikely is a relative and subjective matter as it derives from the limitations of human reason and experience, either individual or collective.[55] Not so long ago, it was considered unlikely for someone to travel from one country to another in a short span of time, and even impossible for anyone to reach the moon. But due to technological advancements, such feats are now easily achievable. In a similar manner, if an authentic ḥadīth describes something which appears difficult to believe, such as the splitting of the moon,[56] it is incorrect to discard it as an impossibility. Failure to appreciate its meaning can stem from a myriad of factors. Khalīl Mullā Khāṭir aptly points out, “It seems that skeptics of Ḥadīth have confused what is impossible with what is unacceptable to the Western worldview.”[57]

That many of the same ḥadīths modern critics regard as problematic were already discussed in detail by the greatest Islamic minds is often overlooked in these discussions. The difference between classical Muslim scholars and modern critics is the perspective with which the two groups look at the objection. Traditional scholars were not oblivious to scientific realities nor blind to logical fallacies—many, in fact, were actively involved in the rational and scientific fields.[58] However, they had a more robust conception of revelation as a purveyor of actual knowledge and truth about the world, while modern detractors usually presume a more empiricist and rationalist epistemology which tends to reduce the role of revelation in providing knowledge, as well as being overly quick to subordinate the interpretation of revelation to the independent conclusions of reason and science. When presented with ḥadīths that at first blush seem problematic, the reader is advised to bear in mind the guidelines outlined above, and not dismiss them summarily without a second thought.

____________________________________________

[1] Al-Ghazālī, al-Iqtiṣād, p. 66.

[2] Q 21:10.

[3] Q 5:103.

[4] “[T]he Qurʾanic mode of thinking is not empirical or rationalist, historical or systematic apodictic or pedagogical, analytical or descriptive. It is none of them and yet all of them at once. It combines conceptual analysis with moral judgment, empirical observation with spiritual guidance, historical narrative with eschatological expectation, and abstraction with imperative command.” See Ibrahim Kalin, Reason and Rationality in the Qurʾān, p. 9.

[5] Jalāl al-Dīn al-Suyūṭī writes, “There is no demonstration, argumentation, disjunction, or admonition built upon the general categories of knowledge afforded by reason and revelation that the Book of Allah has failed to articulate; it has mentioned them, however, according to the customary [speech habits] of the Arabs and not in accordance with the intricate methods of the theologians.” See al-Suyūṭī, al-Itqān fī ʿUlūm al-Qurʾān, vol. 4, p. 60.

[6] See al-Ghazālī, Qānūn al-Taʾwīl, p. 9.

[7] See Fūdah, al-Sharḥ al-Kabīr, vol. 1, pp. 38-40.

[8] When vocalized as mukhtalif (active participle) it refers to ḥadīths that ostensibly conflict with one another; when vocalized as mukhtalaf (verbal noun) it refers to the difference between the apparently contradictory ḥadīths. See Khayyāṭ, Mukhtalif al-Ḥadīth bayn al-Muḥaddithīn wa al-Uṣūliyyīn wa al-Fuqahāʾ, pp. 25-26.

[9] Abū Shahbah, al-Wasīṭ fī ʿUlūm wa Muṣṭalaḥ al-Ḥadīth, pp. 442-43.

[10] On whether Ikhtilāf al-Ḥadīth is an independent work or part of al-Umm, see al-Sūsah, Manhaj al-Tawfīq wa al-Tarjīḥ, pp. 32-34.

[11] The accurate title of this book is “Bayān Mushkil Ahādīth Rasūl Allāh (ṣallallāhū ʿalayhī wa sallam) wa Istikhrāj mā fīhā min al-Aḥkām wa Nafy al-Taḍād ʿanhā.” See al-ʿAwnī, al-ʿUnwān al-Ṣaḥīḥ li al-Kitāb, pp. 64-65.

[12] Al-Baghdādī, al-Kifāyah, pp. 432-33; cf. al-Haytamī, Ilṣāq ʿUwār al-Hawas, pp. 223-6.

[13] It is not uncommon to find commentaries (e.g. al-Munāwī’s Fayḍ al-Qadīr) expounding on the meanings of ḥadīths that are arguably unreliable. One reason for this is that the commentator did not believe the given ḥadīth to be unreliable or he commented with the hope that if an authentic route of transmission were located later his commentary might be of help. See, for instance, al-Ṭaḥāwī, Sharḥ Maʿānī al-Āthār, vol. 4, p. 331. Beyond this, explanations of such ḥadīths can also be useful since they indirectly provide commentary for material that at times is also found in reliable ḥadīths, for which commentary is not easily accessible.

[14] Ibn al-Jawzī, al-Mawḍūʿāt, vol. 1, p. 189.

[15] Al-Qārī, al-Asrār al-Marfūʿah, p. 217.

[16] Al-Ṭahāwī sets out to explain the apparent problems and disharmony between reports “transmitted from the Prophet (peace and blessings be upon him) via acceptable chains of transmissions related by those of circumspection, honesty, and suitable delivery.” See al-Ṭaḥāwī, Sharḥ Mushkil al-Āthār, vol. 1, p. 6.

[17] Al-Khaṭīb, al-Jāmiʿ li Akhlāq al-Rāwī wa Ādāb al-Sāmiʿ, vol. 2, p. 212.

[18] The route of ʿĀʾishah is cited in Muslim, al-Musnad al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 1007, and the route of Buraydah in Aḥmad, al-Musnad, no. 22998, among others.

[19] The route of Ibn ʿAbbās is cited in al-Bukhārī, al-Adab al-Mufrad, no. 422 and al-Ṭabarānī, al-Muʿjam al-Kabīr, vol. 11, p. 55. The route of Abū Hurayrah is cited in al-Bazzār, al-Musnad, no. 9200; Ibn Mandah, al-Tawḥīd, no. 92; al-Aṣfahānī, Ḥilyat al-Awliyāʾ, vol. 8, p. 307; and al-Bayhaqī, Shuʿab al-Īmān, vol. 13, p. 482.

[20] See Jamīl Abū Sārah, Athar al-ʿIlm al-Tajrībī fī Kashf Naqd al-Ḥadīth al-Nabawī, pp. 212-19.

[21] There is disagreement among the jurists on the sequence of these steps. Although the majority of scholars arrange the steps as outlined here, the sound view in the Ḥanafī school of law is that a person will first seek out abrogation then preference then harmonization. See al-Turkumānī, Dirāsāt, pp. 499-502.

[22] Ibn Rajab, Fatḥ al-Bārī, vol. 5, pp. 155-56; Ibn Ḥazm, al-Iḥkām, vol. 2, p. 21; al-Ṭaḥāwī, vol. 4, p. 274. Related to this is Ibn al-Qayyim’s priceless observation that every time a ḥadīth is reported with multiple, conflicting permutations it is a poor methodology to dismiss them as multiple occurrences, instead of attributing a flaw to one of the transmitters. See Ibn al-Qayyim, Zād al-Maʿād, vol. 2, p. 273. For an extensive study on employing ‘multiple occurrences’ as an interpretive tool for conflicting ḥadīths, see Dr. Ḥamzah al-Bakrī’s “Taʿaddud al-Ḥādithah fī Riwāyāt al-Ḥadīth al-Nabawī.”

[23] Muslim, al-Musnad al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 2099.

[24] Al-Bukhārī, al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 475; Muslim, al-Musnad al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 2100.

[25] Al-Khaṭṭābī, Maʿālim al-Sunan, vol. 4, p. 120; cf. al-Ṭaḥāwī, Sharḥ Maʿānī al-Āthār, vol. 4, p. 280.

[26] Indications that one ḥadīth is abrogated can take several forms: an explicit directive from the Prophet, a statement from a Companion on the Prophet’s final practice, dating the ḥadīths to determine the latter of the two, and the consensus of the community upon one of the ḥadīths. See al-Nawawī, al-Minhāj, vol. 1, p. 35.

[27] Al-Bukhārī, al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 112; Muslim, al-Musnad al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 3004.

[28] Ibn Qutaybah, Taʾwīl Mukhtalif al-Ḥadīth, p. 412; al-Khaṭṭābī, Maʿalim al-Sunan, vol. 4, p. 184.

[29] Al-Nawawī, al-Minhāj, vol. 1, p. 35. On these factors, see al-Ḥasanī, Maʿrifat Madār al-Isnād, p. 87 ff.; al-Turkumānī, Dirāsāt, pp. 509-531.

[30] Al-Bukhārī, al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 608; cf. Ibn Ḥajar, Fatḥ al-Bārī, vol. 2, p. 85.

[31] Al-Nasafī, al-ʿAqīdah al-Nasafiyyah, p. 2.

[32] “Reason, both theoretical and practical, is our accumulated and critically organized common sense and contains a normative kernel of widely accepted values and ultimate ideals.” See Shabbir Akhtar, The Qurʾān and the Secular Mind, p. 58. One has to be cautious not to confuse certain constructions of reason, such as the Aristotelian-Neoplatonic tradition, as synonymous with ‘human reason’ per se. See Sherman Jackson, On the Boundaries of Theological Tolerance in Islam, p. 19 ff.; idem, Islam & the Problem of Black Suffering, pp. 38-40. In the present day, many charges against Islam as being irrational stem from the fact that rationality “as developed in the Islamic intellectual tradition contravenes the main thrust of modern and postmodern notions of rationality that have arisen in the West since the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.” See Kalin, Reason and Rationality in the Qurʾān, p. 2.

[33] In The Outer Limits of Reason, Noson Yanofsky provides fascinating and engaging examples of the limits of reason and its related areas: science, technology, logic, and mathematics. See, for instance, the chessboard and dominos example, the ship of Theseus, Russell’s paradox, and the problem of induction in pp. 2, 31, 85, 236, and 340-45, respectively.

[34] Ibn Taymiyyah, Darʾ Taʿāruḍ al-ʿAql wa al-Naql, vol. 5, p. 297-8; Kalin, Reason and Rationality in the Qurʾān, p. 7.

[35] See Shabbīr al-ʿUthmānī, al-ʿAql wa al-Naql, pp. 87-95. Mawlānā Shabbīr al-ʿUthmānī asks rhetorically: have we applied, say, our sense of touch to the point we touched everything that can be felt or our sense of hearing to the point we heard all there is to hear? When we accept that we have not—and cannot—utilized these senses to their full capacity, how do we then accept to achieve a complete grasp of our rational faculties? See ibid. p. 33. Allah informs mankind about the limits of their knowledge, “You may dislike something although it is good for you, or like something although it is bad for you: Allah knows and you do not” (Q 2:216) and “You have only been given a little knowledge” (Q 17:85).

[36] Ibn Khaldūn writes, “The intellect, indeed, is a correct scale. Its indications are completely certain and in no way wrong. However, the intellect should not be used to weigh such matters as the oneness of God, the other world, the truth of prophecy, the real character of the divine attributes, or anything else that lies beyond the level of the intellect. That would mean to desire the impossible. One might compare it with a man who sees a scale in which gold is being weighed, and wants to weigh mountains in it.” Ibn Khaldūn, The Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History, trans. Franz Rosenthal, vol. 3, p. 38.

[37] See Brown, Misquoting Muhammad, p. 144; idem, Muhammad: A Very Short Introduction, p. 76.

[38] Q 34:28.

[39] Al-Subkī, al-Ashbāh wa al-Naẓāʾir, vol. 2, p. 135. For other qualifications to this maxim, see ibid., p. 136-37.

[40] Ibid.

[41] There is obvious nuance in categorizing the practices (sunan) of the Prophet vis-à-vis their value as legal rulings. Dr. Sulaymān al-Ashqar divides the actions (afʿāl) of the Prophet into ten categories. Among them, actions that were jibillī (innate) [e.g. ordinary activities like walking and sleeping], ʿādī (customary) [e.g. lengthening the hair and wearing certain attire], dunyawī (mundane) [e.g. political strategies] do not allow for more than general permissibility unless external evidence suggests otherwise. See al-Ashqar, Afʿāl al-Rasūl wa Dalālatuhā al-Sharʿiyyah, pp. 215-48. That being said, Shaykh ʿAbd Allah al-Ghumārī explains that legal theorists have stated that a person will be rewarded for following the customary practices of the Prophet (e.g. wearing certain types of clothing or eating certain types of food) out of love and emulation of the Prophet. ʿAbd Allah ibn ʿUmar is on record for his scrupulous emulation of the Prophet even in these matters. See al-Ghumārī, al-Nafḥah al-Ilāhiyyah, p. 157. According to Abū Shāmah al-Maqdisī (d. 665 AH) and Tāj al-Dīn al-Subkī (d.771 AH)—and Ḥadīth scholars in general, as related by al-Ghazālī—emulation in these practices are desirable, albeit the lowest form of desirability (istiḥbāb). See Abū Shāmah, al-Muḥaqqaq min ʿIlm al-Uṣūl, pp. 270-71; ʿAwwāmah, Hujjiyat Afʿāl al-Rasūl, pp. 56-60.

[42] On the use of a figurative reading of ḥadīths as a tool to explain away problematic content, see Jamīl, Athar al-ʿIlm al-Tajrībī, pp. 146-50.

[43] See, for instance, Q 9:67; cf. Ibn Kathīr, Tafsīr Qurʾān al-ʿAẓīm, vol. 4, p. 174.

[44] Al-Tirmidhī, al-Sunan, no. 692.

[45] For a summary of the interpretations of the word ʿArsh, see al-Muṭīʿī, Tawfīq al-Raḥmān, pp. 361-63.

[46] See Q 17:45.

[47] See al-Bukharī, al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 3199; Shafīʿ, Maʿārif al-Qurʾān, vol. 7 pp. 389-82.

[48] Al-Bannūrī, Maʿārif al-Sunan, vol. 5, p. 349.

[49] Al-Dihlawī, Ḥujjat Allāh al-Bālighah, vol. 1, p. 158.

[50] In a fascinating study, Halim Sayoud conducted an author discrimination analysis—where two texts are studied to determine whether they were composed by the same author—comparing the Qurʾān and the ḥadīths recorded in Ṣaḥīḥ al-Bukhārī. By conducting three series of experiments (global form, segmental form, and an automatic author attribution), Sayoud concluded, “First, the two investigated books should have different authors; second, all the segments that are extracted from a unique book appear to have a certain stylistic similarity.” See Sayoud, Halim (2012), Author Discrimination Between the Holy Qurʾān and the Prophet’s Statements, Literary and Linguistic Computing, vol. 27, no. 4, 2012, pp. 427-44. The second conclusion of this study demonstrates that despite the frequent usage of paraphrasing when transmitting the Prophet’s words (al-riwāyah bi al-maʿnā), the ḥadīths maintained an overall degree of stylistic consistency. See Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., p. 12.

[51] Ibn ʿAdī, al-Kāmil, vol. 2, p. 403.

[52] Al-Mundhirī, al-Targhīb wa al-Tarhīb, vol. 4, p. 75, no. 4855.

[53] Brown, Hadith, 2nd ed., p. 12.

[54] Under the ḥadīth “Whoever deceives is not from among us,” al-Khaṭṭābī writes, “That is, he is not upon our path. He intends thereby that the person who deceives his brother and does not take his best interest to mind has failed to follow me and hold unto my lifestyle. Some have understood this as an exclusion of the person from Islām, but this interpretation is not sound.” See al-Khaṭṭābī, Maʿālim al-Sunan, vol. 3, p. 118.

[55] See al-Sibāʿī, Al-Sunnah wa Makānatuhā fi al-Tashrīʿ al-Islāmī, pp. 51-52; cf. Mullā Khāṭir, al-Iṣābah fī Ṣiḥḥat Ḥadīth al-Dhubābah, p. 101; ʿAbd Allah al-Ghumārī, al-Qawl al-Jazl fī mā lā Yuʿdhar fīhī bi al-Jahl, p. 11.

[56] Al-Bukhārī, al-Jāmiʿ al-Ṣaḥīḥ, no. 3636/3868; cf. Jamīl, Athar al-ʿIlm al-Tajrībī, pp. 84-8.

[57] Mullā Khāṭir, al-Iṣābah fī Ṣiḥḥat Ḥadīth al-Dhubābah, p. 102; cf. Brown, The Rules of Matn Criticism, p. 393-94.

[58] The Muslim scientist and physician Ibn al-Nafīs (d. 687 AH) is one example. Not only was he a skilled physician and scientist, second only to Ibn Sīnā (Avicenna), he also wrote a book on Ḥadīth nomenclature. See al-Subkī, al-Ṭabaqāt al-Shāfiʿiyyah al-Kubrā, vol. 8, p. 305; Meyerhof, M. and Schacht, J., “Ibn al-Nafīs,” in the Encyclopedia of Islam, Second Edition.