Defending The Transgressed By Censuring the Reckless Against the Killing of Civilians

Fatwa according to the maddhab of Imam ash-Shafi'i by Shaykh Muhammad Afifi al-Akiti

Foreword by Shaykh Gibril Fouad Haddad

In the name of God, the All-Beneficent, the Most Merciful.

Gentle reader, I am honored to present the following fatwa or legal verdict by a qualified Muslim Scholar against the killing of civilians by the Oxford-based Malaysian jurist of the Shafi`i School and my inestimable teacher, Shaykh Muhammad Afifi al-Akiti, titled Defending the Transgressed by Censuring the Reckless against the Killing of Civilians.

The Shaykh authored it in a few days, after I asked him to offer some guidance on the issue of targeting civilians and civilian centers by suicide bombing in response to a pseudo-fatwa by a deviant UK-based group which advocates such crimes. Upon reading Shaykh Afifi’s fatwa, do not be surprised to find that you have probably never before seen such clarity of thought and expression together with breadth of knowledge of Islamic Law applied (by a non-native speaker) to define key Islamic concepts pertaining to the conduct of war and its jurisprudence, its arena and boundaries, suicide bombing, the reckless targeting of civilians, and more. May it bode the best start to true education on the impeccable position of Islam squarely against terrorism in anticipation of the day all its culprits are brought to justice.

I have tried to strike the keynote of this Fatwa in a few lines of free verse, mostly to express my thanks to our Teacher but also to seize the opportunity of such a long-expected response to remind myself of the reasons why I embraced Islam in the first place.

A TAQRIZ – HUMBLE COMMENDATION:

Praise to God Whose Law shines brighter than the sun!

Blessings and peace on him who leads to the abode of peace!

Truth restores honor to the Religion of goodness.

Patient endurance lifts the oppressed to the heights

While gnarling mayhem separates like with like:

The innocent victims on the one hand and, on the other,

Silver-tongued devils and wolves who try to pass for just!

My God, I thank You for a Teacher You inspired

With words of light to face down Dajjal’s advocates.

Allāh bless you, Ustadh Afifi, for Defending the Transgressed

By Censuring the Reckless Against the Killing of Civilians!

Let the powers that be and every actor-speaker high and low

Heed this unique Fatwa of knowledge and responsibility.

Let every lover of truth proclaim, with pride once more,

What the war-mongers try to bury under lies and bombs:

Islam is the truth, the Rule of Law, justice and right!

Murderous suicide is never martyrdom but rather perversion,

Just as no flag on earth can ever justify oppression.

And may God save us from all criminals, East and West!

Shaykh G.F. Haddad

Day of Jumu`a after `Asr

1 Rajab al-Haram 1426 AH

5 August 2005 CE

Sultanate of Brunei, Darussalam

|

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________

|

| In the name of Allah, the Beneficent, the Merciful |

Initial question

"If you have some time to address this delicate issue for the benefit of this mercied Ummah which is reeling in fitnah day in and day out, perhaps a few blessed words might use a refutation of the following text as a springboard?

I would like you to read the following article which highlights some of the problems we are facing, and [shows] why it is quite possible that young Muslims turn to extremism. The article was issued by “Al-Muhajiroun” not long ago, headed by Omar Bakri Mohammed, and whatever our reservations about the man, it is the content I am more concerned about, and it is possibly these types of writings which need to be confronted head-on."

Excerpt from an Article by a Group called ‘al-Muhajiroun’:

Shaykh Muhammad Afifi al-Akiti's FatwaAQD UL-AMAAN: THE COVENANT OF SECURITY

The Muslims living in the West are under a covenant of security, it is not allowed for them to fight anyone with whom they have a covenant of security, abiding with the covenant of security is an important obligation for all Muslims. However for those Muslims living abroad, they are not under any covenant with the kuffar in the west, so it is acceptable for them to attack the non-Muslims in the west whether in retaliation for constant bombing and murder taking place all over the Muslim world at the hands of the non-Muslims, or if it an offensive attack in order to release the Muslims from the captivity of the kuffar. For them, attacks such as the September 11th Hijackings is a viable option in jihad, even though for the Muslims living in America who are under covenant, it is not allowed to do operations similar to those done by the magnificent 19 on the 9/11.

In the name of God, the most Merciful and Compassionate. Praise be to God Who sets the boundaries of war and does not love transgressors! Blessings and peace on the General of the Community, the most patient of men in the face of the harm of enemies, with perfect chivalry and complete manliness, and upon all his Family, Companions, and Army!

This is a collection of masā’il, entitled: Mudāfi’ al-Mazlûm bi-Radd al-Muhāmil ‘alā Qitāl Man Lā Yuqātil [Defending the Transgressed, by Censuring the Reckless against the Killing of Civilians], written to response to the fitnah reeling this mercied Ummah, day in and day out, which is partly caused by those who, wilfully or not, misunderstand the legal discussions of the chapter on warfare outside its proper contexts (of which the technical fiqh terminology varies with bāb: siyar, jihād, or qitāl), which have been used by them to justify their wrong actions. May Allāh open our eyes to the true meaning [haqīqa] of sabr and to the fact that only through it can we successfully endure the struggles we face in this dunyā, especially during our darkest hours; for indeed He is with those who patiently endure tribulations!

There is no khilāf that all the Shafi’i fuqahā’ of today and other Sunni specialists in the Sacred Law from the Far East to the Middle East reject outright [mardûd] the above opinion and consider it not only an anomaly [shādhdh] and very weak [wāhin] but also completely wrong [bātil] and a misguided innovation [bid’a dalāla]: the ‘amal cannot at all be adopted by any mukallaf. It is regrettable too that the above was written in a legal style at which any doctor of the Law should be horrified and appalled (since it is an immature yet persuasive attempt to mask a misguided personal opinion with authority from fiqh, and an effort to hijack our Law by invoking one of the many qadāya of this bāb while recklessly neglecting others). It should serve to remind the students of fiqh of the importance of the forming in one’s mind and being aware throughout of the thawābit and the dawābit when reading a furû’ text, in order to ensure that those principal rules have not been breached in any given legal case.

The above opinion is problematic in three legal particulars [fusûl]:

- the target [maqtûl]: without doubt, civilians;

- the authority for carrying out the killing [āmir al-qitāl]: as no Muslim authority has declared war, or if there has been such a declaration there is at the time a ceasefire [hudna]; and

- the way in which the killing is carried out [maqtûl bih]: since it is either harām and is also cursed as it is suicide [qātil nafsah], or at the very least doubtful [shubuhāt] in a way such that it must be avoided by those who are religiously scrupulous [wara’]. Any sane Muslim who would believe otherwise and think the above to be not a crime [jināya] would be both reckless [muhmil] and deluded [maghrûr]. Instead, whether he realizes it or not, by doing so he would be hijacking rules from our Law which are meant for the conventional (or authorized) army of a Muslim state and addressed to those with authority over it (such as the executive leaders, the military commanders and so forth), but not to individuals who are not connected to the military or those without the political authority of the state [dawla].

Fasl I. The Target: Maqtûl

The proposition: “so it is acceptable for them to attack the non-Muslims in the west”, where “non-Muslims” can be taken to mean, and indeed does mean in the document, non-combatants, civilians, or in the terminology of fiqh: those who are not engaged in direct combat [man la yuqātilu].

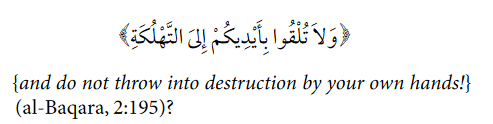

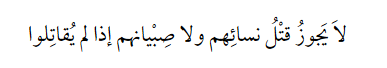

This opinion violates a well known principal rule [dābit] from our Law:

|

“la yajuzu qatlu nisa’ihim wa-la sibyanihim idhh lam yuqatilu”

|

[it is not permissible to kill their [i.e., the opponents’] women and children if they are not in direct combat.]

This is based on the Prophetic prohibition on soldiers from killing women and children, from the well known hadith of Ibn ‘Umar (may Allāh be pleased with them both!) related by the Imam Malik, al-Shafi’i, Ahmad, al-Bukhari, Muslim, Ibn Majah, Abu Dawud, al-Tirmidhi, al-Bayhaqi and al-Baghawi (may Allāh be well pleased with them all) and other hadiths.

Imam al-Subki (may Allāh be pleased with him) made it unequivocally clear what scholars have understood from this prohibition in which the standard rule of engagement taken from it is that:

“[a Muslim soldier] may not kill any women or any child-soldiers unless they are in combat directly, and they can only be killed in self-defence” [al-Nawawi, Majmû’, 21:57].It goes without saying that men and innocent bystanders who are not direct combatants are also included in this prohibition. The nature of this prohibition is so specific and well-defined that there can be no legal justification, nor can there be a legitimate shar’ī excuse, for circumventing this convention of war by targeting non-combatants or civilians whatsoever, and that the hukm shar’ī of killing them is not only harām but also a Major Sin [Kabira] and contravenes one of the principal commandments of our way of life.

Fasl II. The Authority: Āmir al-Qitāl

The proposition: “so it is acceptable for them to attack the non-Muslims in the west whether in retaliation for constant bombing and murder taking place all over the Muslim world at the hands of the non-Muslims,” where it implies that a state of war exist with this particular non-Muslim state on account of its being perceived as the aggressor.

This opinion violates the most basic rules of engagement from our Law:

| “amru l-jihadi mawkulun ila l-imami wa-ijtihadihi wa-yalzamu r-ra’iyyata ta’atuhu fima yarahu min dhalika” |

[The question of declaring war (or not) is entrusted to the executive authority and to its decision: compliance with that decision is the subject’s duty with respect to what the authority has deemed appropriate in that matter.]

|

| “wa-li-imamin aw amirin khiyarun bayna l-kaffi wa l-qitali” |

[The executive or its subordinate authority has the option of whether or not to declare war]

Decisions of this kind for each Muslim state, such as those questions dealing with ceasefire [‘aqd al-hudna], peace settlement [‘aqd al-amān] and the judgment on prisoners of war [al-ikhtār fi asīr] can only be dealt with by the executive or political authority [imām] or by a subordinate authority appointed by the former authority [amīr mansûbin min jihati l-imām]. This is something Muslims take for granted from the authority of our naql [scriptures] such that none will reject it except those who betray their ‘aql [intellect]. The most basic legal reason [‘illa aslīyya] is that this matter is one that involves the public interest, and thus consideration of it belongs solely to the authority:

| ||

| "li-anna hadha l-amra mina l-masalihi l-‘ammati allati yakhtassu l-imami bi-n-nazari fi-ha." |

|

| "tasarrufu l-imami ‘ala r-ra’iyyati manutun bi l-maslahati" |

[The decisions of the authority on behalf of the subjects are dependent upon the public good]

And:

| "fa-yaf’alu l-imamu wujuban al-ahazza li-l-muslimina li-ijtihadihi" |

[So the authority must act for the greatest advantage of (all of) the Muslims in making its judgement]

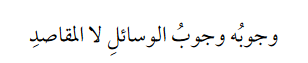

Nasiha: Uppermost in the minds of the authority during their deliberation over whether or not to wage war should be the awareness that war is only a means and not the end. Hence, if there are other ways of achieving the aim, and the highest aim is the right to practice our religion openly (as is indeed the case in modern day Spain, for example, unlike in medieval Reconquista Spain), then it is better [awlā] not to go to war. This has been expressed in a few words by Imam al-Zarkashī (may Allāh be pleased with him):

|

| "wujubuhu wujubu l-wasa’ili la l-maqasidi" |

[Its necessity is the necessity of means, not ends.]

The upshot is, whether one likes it or not, the decision and discretion and right to declare war or jihād for Muslims lie solely with the various authorities as represented today by the respective Muslim states – and not with any individual, even if he is a scholar or a soldier (and not just anyone is a soldier or a scholar) – in the same way that an authority (such as the qādī in a court of law: mahkamah) is the only one with the right to excommunicate or declare someone an apostate [murtad]. Otherwise, the killing would be extra-judicial and unauthorized.

Even during the period of the Ottoman caliphate, for example, another Muslim authority elsewhere, such as in the Indian subcontinent, could have been engaged in a war when at the same time the Khalifa’s army was at peace with the same enemy. This is how it has been throughout our long history, and this is how it will always be, and this is the reality on the ground.

The proposition: “attacks such as the September 11th Hijackings is a viable option in jihād,” where such attacks employ tactics – analogous to the Japanese “kamikaze” missions during the Second World War – that have been described variously as self-sacrificing or martyrdom or suicide missions.

There is no question among scholars, and there is no khilāf on this question by any qādī, muftī or faqīh, that this proposition and those who accept it are without doubt breaching the scholarly consensus [mukhālifun li-l-ijmā’] of the Muslims since it resulted in the killing of non-combatants; moreover, the proposition is an attempt to legitimize the killing of indisputable non-combatants.

As for the kamikaze method and tactic in which it was carried out, there is a difference of opinion with some jurists as to whether or not it constitutes suicide, which is not only harām but also cursed. In this, there are further details. (Note that in all of the following cases, it is already assumed that the target is legitimate – i.e., a valid military target – and that the action is carried out during a valid war when there is no ceasefire [fi hāl al-harb wa-lā l-hudnata fihi], just as with the actual circumstance of the Japanese kamikaze attacks.)

Tafsīl I: If the attack involves a bomb placed on the body or placed so close to the bomber that when the bomber detonates it the bomber is certain [yaqīn] to die, then the More Correct Position [Qawl Asahh] according to us is that it does constitute suicide. This is because the bomber, being also the maqtûl [the one killed], is unquestionably the same as the qātil [the immediate and active agent that kills] = qātil nafsah [self-killing, i.e. suicide].

Furu’: If the attack involves a bomb (such as the lobbing of a grenade and the like), but the attacker thinks that when it is detonated , it is uncertain [zann] whether he will die in the process or survive the attack, then the Correct Position [Qawl Sahīh] is that this does not constitute suicide, and were he to die in this selfless act, he becomes what we properly call a martyr or hero [shahīd]. This is because the attacker, were he to die, is not the active, willing agent of his own death, since the qātil is probably someone else.

An example [sûra] of this is: when in its right place and circumstance, such as in the midst of an ongoing fierce battle against an opponent’s military unit, whether ordered by his commanding officer or whether owing to his own initiative, the soldier makes a lone charge and as a result of that initiative manages to turn the tide of the day’s battle but dies in the process (and not intentionally at his own hand). That soldier died as a hero (and this circumstance is precisely the context of becoming a shahīd – in Islamic terminology – as he died selflessly). If he survives, he wins a Medal of Honour or at the least becomes an honoured war hero and is remembered as a famous patriot (in our terminology, becoming a true mujāhid ).

This is precisely the context of the mas’ala concerning the “lone charger” [al-hājim al-wahīd] and the meaning of putting one’s life in danger [al-taghrīr bil-nafs] found in all of the fiqh chapters concerning warfare. The Ummah’s Doctor Angelicus, Imām al-Ghazālī (may Allāh be pleased with him) provides the best impartial summation:

Tafsīl II: If the attack involves ramming a vehicle into a military target and the attacker is certain to die, precisely like the historical Japanese kamikaze missions, then our jurists have disagreed over whether it does or does not constitute suicide.

Qawl A: Those who consider it a suicide argue that there is the possibility [zannī] that the maqtûl is the same as the qātil (as in Tafsīl I above) and would therefore not allow for any other qualification whatsoever, since suicide is a cursed sin.

Qawl B: Whereas those who consider otherwise, even with the possibility that the maqtûl is the same as the qātil, will allow some other qualification such as the possibility that by carrying it out the battle of the day could be won. There are further details in this alternative position, such as that the commanding officer does not have the right to command anyone under him to perform this dangerous mission, so that were it to be sanctioned, it could only be when it is not under anyone else’s orders and is the lone initiative of the concerned soldier (such as in defiance of the standing orders of his commanding officer).

The first of the two positions is the Preferred Position [muttajih] among our jurists, as the second is the rarer because of the vagueness of a precedent, and its legal details are fraught with further difficulties and ambiguities, and its opposing position [muqābil] carries such a weighty consequence (namely, that of suicide, for which there is ijmā’ that the one who commits suicide will be damned to committing it eternally forever).

In addition to this juristic preference, the first position is also preferable and better since it is the original or starting state [asl], and by invoking the well-known and accepted legal principle:

Finally, the first position is religiously safer, since owing to the ambiguity itself of the legal status of the person performing the act – whether it will result in the maqtûl being also the qātil – and since there is doubt and uncertainty over the possibility of its either being or not being the case, then this position falls under the type of doubtful matters [shubuhāt] of the kind [naw’] that should be avoided by those who are religiously scrupulous [wara’]. And here, the wisdom of our wise Prophet ﷺ is illuminated from the Hadith of al-Nu’man (may Allāh be well pleased with him):

Wa-Llāhu a’lam bis-sawāb! [God knows best what is right!]

Fa’ida: The original ruling [al-asl] for using a bomb (the medieval precedents: Greek fire [qitāl bil-nār or ramy al-naft] and catapults [manjanīq]) as a weapon is that it is makrûh [offensive] because it kills indiscriminately [ya’ummu man yuqātilû wa-man lā yuqātilû], as opposed to using rifles (medieval example: a single bow and arrow). If the indiscriminate weapon is used in a place where there are civilians, it becomes harām except when used as a last resort [min darûra] (and of course, by those military personnel authorised to do so).

As to those who may still be persuaded by it and suppose that the action is something that can be excused on the pretext that there is scholarly khilāf on the details of Tafsīl II from Fasl III above (and that therefore, the ‘amal itself could at the end of the day be accommodated by invoking the guiding principle that one should be flexible with regards to legal controversies [masā’il khilāfiyya] and agree to disagree); know then there is no khilāf among scholars that that rationale does not stand, since it is well known that:

Since at the very least, it is agreed upon by all that killing non-combatants is prohibited, there is no question whatsoever that the ‘amal overall is outlawed.

The qā’ida, which is expressed very tersely above, means, understood correctly, that an action about which there is khilāf may be excused, while an action that contravenes the Ijmā’ is categorically rejected.

If it is said:

We say: On a joking note (but ponder over this so your hearts may be opened!): the authority is not with what Islam says but with what Allāh (Exalted is He) and His Messenger ﷺ have said!

But seriously: the answer is absolutely no; for even a novice student of fiqh would be able to see that the first dābit above concerns already a non-Muslim opponent in the case of a state of war having been validly declared by a Muslim authority against a particular non-Muslim enemy, even when that civilian is a subject or in the care [dhimma] of the hostile non-Muslim state [Dār al-Harb]. If this is the extent of the limitation to be observed with regards to non-Muslim civilians associated with a declared enemy force, what higher standard will it be in cases if it is not a valid war or when the status of war becomes ambiguous? Keep in mind that there are more than 100 Verses in the Qur’ān commanding us at all times to be patient in the face of humiliation and to turn away from violence [al-i’rād ‘ani l-mushrikīn wa l-sabr ‘alā adhā l-a’dā’], while there is only one famous Verse in which war (which does not last forever) becomes an option (in our modern context: for a particular Muslim authority and not an individual), when a particular non-Muslim force has drawn first blood.

Furu’: If the attack involves a bomb (such as the lobbing of a grenade and the like), but the attacker thinks that when it is detonated , it is uncertain [zann] whether he will die in the process or survive the attack, then the Correct Position [Qawl Sahīh] is that this does not constitute suicide, and were he to die in this selfless act, he becomes what we properly call a martyr or hero [shahīd]. This is because the attacker, were he to die, is not the active, willing agent of his own death, since the qātil is probably someone else.

An example [sûra] of this is: when in its right place and circumstance, such as in the midst of an ongoing fierce battle against an opponent’s military unit, whether ordered by his commanding officer or whether owing to his own initiative, the soldier makes a lone charge and as a result of that initiative manages to turn the tide of the day’s battle but dies in the process (and not intentionally at his own hand). That soldier died as a hero (and this circumstance is precisely the context of becoming a shahīd – in Islamic terminology – as he died selflessly). If he survives, he wins a Medal of Honour or at the least becomes an honoured war hero and is remembered as a famous patriot (in our terminology, becoming a true mujāhid ).

This is precisely the context of the mas’ala concerning the “lone charger” [al-hājim al-wahīd] and the meaning of putting one’s life in danger [al-taghrīr bil-nafs] found in all of the fiqh chapters concerning warfare. The Ummah’s Doctor Angelicus, Imām al-Ghazālī (may Allāh be pleased with him) provides the best impartial summation:

“If it is said: What is the meaning of the words of the Most High:

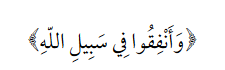

We say: There is no difference [of opinion amongst scholars] regarding the lone Muslim [soldier] who charges into the battle-lines of the [opposing] non-Muslim [army that is presently in a state of war with his army and is facing them in a battle] and fights [them] even if he knows that he will almost certainly be killed. The case might be thought to go against the requirements of the Verse, but that is not so. Indeed, Ibn ‘Abbās (may Allāh be well pleased with both of them!) says: [the meaning of] “destruction” is not that [incident]. Instead, [its meaning] is to neglect providing [adequate] supplies [nafaqa: for the military campaign; and in the modern context, the state should provide the arms and equipment and so forth for that for which all of this is done] in obedience to God [as in the first part of the Verse which says:

{And spend for the sake of God!} (al-Baqara, 2:195)

It is clear that this selfless deed which any modern soldier, Muslim or non-Muslim, might perform in battle today is not suicide. It may hyperbolically be described as a ‘suicidal’ attack, but to endanger one’s life is one thing and to commit suicide during the attack is obviously another. And as the passage shows, it is possible to have both situations: an attack that is taghrīr bil-nafs, which is not prohibited; and an attack that is of the tahluka-type, which is prohibited.That is, those who fail to do that will destroy themselves. [In another Sahābī authority:] al-Barā’ Ibn ‘āzib [al-Ansāri (may Allāh be well pleased with them both!)] says: [the meaning of] “destruction” is [a Muslim] committing a sin and then saying: ‘my repentance will not be accepted’. [A tābi’ī authority] Abû ‘Ubayda says: it [the meaning of “destruction”] is to commit a sin and then not perform a good deed after it before he perishes. [Ponder over this!]

In the same way that it is permissible [for the Muslim soldier in the incident above] to fight the non-Muslim [army] until he is killed [in the process], that [extent and consequence] is also permissible for him [i.e., the enforcer of the Law, since the `ā’id (antecedent) here goes back to the original pronoun [dāmir al-asl] for this bāb: the muhtasib or enforcer, such as the police] in [matters of] law enforcement [hisba].

However, [note the following qualification (qayd):] were he to know [zanni] that his charge will not cause harm to the non-Muslim [army], such as the blind or the weak throwing himself into the [hostile] battle-lines, then it is prohibited [harām], and [this latter incident] is included under the general meaning [‘umûm] of “destruction” from the Verse [for in this case, he will be literally throwing himself into destruction].

It is only permissible for him to advance [and suffer the consequences] if he knows that he will be able to fight [effectively] until he is killed, or knows that he will be able to demoralize the hearts and minds of the non-Muslim [army]: by their witnessing his courage and by their conviction that the rest of the Muslim [army] are [also] selfless [qilla al-mubāla] in their loyalty to sacrifice for the sake of God [the closest modern non-Muslim parallel would be ‘to die for one’s country’]. By this, their will to fight [shawka] will become demoralized [and so this may cause panic and rout them and thereby be the cause of their battle-lines to collapse].”

Source: [al-Ghazali, Ihya’, 2:315-6]

Tafsīl II: If the attack involves ramming a vehicle into a military target and the attacker is certain to die, precisely like the historical Japanese kamikaze missions, then our jurists have disagreed over whether it does or does not constitute suicide.

Qawl A: Those who consider it a suicide argue that there is the possibility [zannī] that the maqtûl is the same as the qātil (as in Tafsīl I above) and would therefore not allow for any other qualification whatsoever, since suicide is a cursed sin.

Qawl B: Whereas those who consider otherwise, even with the possibility that the maqtûl is the same as the qātil, will allow some other qualification such as the possibility that by carrying it out the battle of the day could be won. There are further details in this alternative position, such as that the commanding officer does not have the right to command anyone under him to perform this dangerous mission, so that were it to be sanctioned, it could only be when it is not under anyone else’s orders and is the lone initiative of the concerned soldier (such as in defiance of the standing orders of his commanding officer).

The first of the two positions is the Preferred Position [muttajih] among our jurists, as the second is the rarer because of the vagueness of a precedent, and its legal details are fraught with further difficulties and ambiguities, and its opposing position [muqābil] carries such a weighty consequence (namely, that of suicide, for which there is ijmā’ that the one who commits suicide will be damned to committing it eternally forever).

In addition to this juristic preference, the first position is also preferable and better since it is the original or starting state [asl], and by invoking the well-known and accepted legal principle:

|

| "al-khuruju mina l-khilafi mustahabbun" |

[To avoid controversy is preferable.]

Finally, the first position is religiously safer, since owing to the ambiguity itself of the legal status of the person performing the act – whether it will result in the maqtûl being also the qātil – and since there is doubt and uncertainty over the possibility of its either being or not being the case, then this position falls under the type of doubtful matters [shubuhāt] of the kind [naw’] that should be avoided by those who are religiously scrupulous [wara’]. And here, the wisdom of our wise Prophet ﷺ is illuminated from the Hadith of al-Nu’man (may Allāh be well pleased with him):

|

| “fa-mani ttaqa sh-shubuhati istabra’a li-dinihi wa ‘irdihi” |

[He who saves himself from doubtful matters will save his religion and his honour.]

(Related by Ahmad, al-Bukhari, Muslim, al-Tirmidhi, Ibn Majah, al-Tabarani, and al-Bayhaqi with variants.)

Fa’ida: The original ruling [al-asl] for using a bomb (the medieval precedents: Greek fire [qitāl bil-nār or ramy al-naft] and catapults [manjanīq]) as a weapon is that it is makrûh [offensive] because it kills indiscriminately [ya’ummu man yuqātilû wa-man lā yuqātilû], as opposed to using rifles (medieval example: a single bow and arrow). If the indiscriminate weapon is used in a place where there are civilians, it becomes harām except when used as a last resort [min darûra] (and of course, by those military personnel authorised to do so).

Hāsil

From the consideration of the foregoing three legal particulars, it is evident that the opinion expressed regarding the ‘amal in the above article is untenable by the standards of our Sacred Law.

|

| "la yunkaru l-mukhtalafu fihi wa-innama yunkaru l-mujma’u ‘alayhi" |

[The controversial cannot be denied; only (breach of) the unanimous can be denied.]

The qā’ida, which is expressed very tersely above, means, understood correctly, that an action about which there is khilāf may be excused, while an action that contravenes the Ijmā’ is categorically rejected.

Masā’il Mufassala

Question I

If it is said:

“I have heard that Islam says the killing of civilians is allowed if they are non-Muslims.”

We say: On a joking note (but ponder over this so your hearts may be opened!): the authority is not with what Islam says but with what Allāh (Exalted is He) and His Messenger ﷺ have said!

But seriously: the answer is absolutely no; for even a novice student of fiqh would be able to see that the first dābit above concerns already a non-Muslim opponent in the case of a state of war having been validly declared by a Muslim authority against a particular non-Muslim enemy, even when that civilian is a subject or in the care [dhimma] of the hostile non-Muslim state [Dār al-Harb]. If this is the extent of the limitation to be observed with regards to non-Muslim civilians associated with a declared enemy force, what higher standard will it be in cases if it is not a valid war or when the status of war becomes ambiguous? Keep in mind that there are more than 100 Verses in the Qur’ān commanding us at all times to be patient in the face of humiliation and to turn away from violence [al-i’rād ‘ani l-mushrikīn wa l-sabr ‘alā adhā l-a’dā’], while there is only one famous Verse in which war (which does not last forever) becomes an option (in our modern context: for a particular Muslim authority and not an individual), when a particular non-Muslim force has drawn first blood.

Question II

If it is said:

“What about the verse of the Qur’an which says {...kill the unbelievers wherever you find them} and the Sahih Hadith which says ‘I have been ordered to fight against the people until they testify’?”

We say: It is well known among scholars that the following verse,

|

| {Kill the idolaters wherever you find them} (al-Tawbah, 9:5) |

..is in reference to a historical episode: those among the Meccan Confederates who breached the Treaty of Hudaybiyya [Sulh al-Hudaybiyya] which led to the Conquest of Mecca [Fath Makkah], and that therefore, no legal rulings, or in other words, no practical or particular implications, can be derived from this Verse on its own. The Divine Irony and indeed Providence from the last part of the Verse, {wherever you find them} – which many of our mufassirs [exegetes] understood in reference to place (i.e., attack them whether inside the Sacred Precinct or not) – is that the victory against the Meccans happened without a single battle taking place, whether inside the Sacred Precinct or otherwise, rather, there was a general amnesty [wa-mannun ‘alayhi bi-takhliyati sabīlihi or naha ‘an safki d-dima’] for the Jāhilī Arabs there. Had the Verse not been subject to a historical context, then you should know that it is of the general type [‘amm] and that it will therefore be subject to specification [takhsīs] by some other indication [dalīl]. Its effect in lay terms, were it not related to the Jahilī Arabs, is that it can only refer to a case during a valid war when there is no ceasefire.

Among the well known exegeses of “al-mushrikīn” [idolators] from this Verse are:

- “al-nākithīna khāssatan” [specifically, those who have breached (the Treaty)] [al-Nawawi al-Jawi, Tafsīr, 1:331];

- “al-ladhīna yuharibunakum” [those who have declared war against you] [Qādi Ibn ‘Arabi, Ahkām al-Qur’ān, 2:889]; and

- “khāssan fī mushkrikī l-‘arabi dûna ghayrihim” [specifically, the Jāhilī Arabs and not anyone else] [al-Jassās, Ahkām al-Qur’ān, 3:81].

As for the meaning of “people” [al-nās] in the above well-related Hadith, it is confirmed by Ijmā’ that it refers to the same “mushrikīn” as in the Verse of Sura al-Tawbah above, and therefore what is meant there is only the Jāhilī Arabs [muskhrikû l-‘arab] during the closing days of the Final Messenger and the early years of the Righteous Caliphs and not even to any other non-Muslims.

In sum, we are not in a perpetual state of war with non-Muslims. On the contrary, the original legal status [al-asl] is a state of peace, and making a decision to change this status belongs only to a Muslim authority who will in the Next World answer for their ijtihād and decision; and this decision is not divinely charged to any individuals – not even soldiers or scholars – and to believe otherwise would go against the well-known rule in our Law that a Muslim authority could seek help from a non-Muslim with certain conditions, including, for example, that the non-Muslim allies are of goodwill towards the Muslims:

|

| "la-yast’inu bi-mushkrikin illa bi-shurutin ka-an takuna niyyatuhu hasanatan li-l-muslimina" |

Question III

If it is said:

“I have heard a scholar say that ‘Israeli women are not like women in our society because they are militarised’. By implication, this means that they fall into the category of women who fight and that this makes them legitimate targets but only in the case of Palestine.”

We say:

No properly schooled jurists from any of the Four Schools [madhahib] would say this as a legal judgement if they faithfully followed the juridical processes of the orthodox Schools relating to this bāb; for if it is true that the scholar made such a statement and meant it in the way you’ve implied, then not only does this violate the well-known principal rule above (Fasl I: “It is not permissible to kill their women and children if they are not in direct combat”), but the supposed remarks also show a lack of sophistication in the legal particulars. If this is the case, then it has to be said here that this is not among the masā’il khilāfiyya, about which one can afford to agree to disagree, since it is outright wrong by the principles and the rules from our usûl and furû’.

Let us restate the dābit again, as our jurists have succinctly summarised its rule of engagement: a soldier can only attack a female or (if applicable) child soldier (or a male civilian) in self-defence and only when she herself (and not someone else from her army) is engaged in direct combat. (As for male soldiers, it goes without saying that they are considered combatants as soon as they arrive on the battlefield even if they are not in direct combat – provided of course that the remaining conventions of war have been observed throughout, and that all this is during a valid war when there is no ceasefire.)

Not only is this strict rule of engagement already made clear in our secondary legal texts, but this is also obvious from the linguistic analysis of the primary proof-texts used to derive this principal rule. Hence, the form of the verb used in the scriptures, yuqātilu, is of the mushāraka-type, so that the verb denotes a direct or a personal or a reciprocal relationship between two agents: the minimum for which is one of them making an effort or attempt to act upon the other. The immediate legal implication here is that one of the two can only even be considered a legitimate target when there is a reciprocal or direct relationship.

In reality [wāqi’], this is not what happens on the ground (since the bombing missions are offensive in nature – they are not targeting, for example, a force that is attacking an immediate Muslim force; but rather the attack is directed at an overtly non-military target, so the person carrying it out can only be described as attacking it – and the target is someone unknown until only seconds before the mission reaches its termination).

In short, even if these women are soldiers, they can only be attacked when they are in direct combat and not otherwise. In any case, there are other overriding particulars to be considered and various conditions to be observed throughout, namely, that it must be during a valid state of war when there is no ceasefire.

Question IV

If it is said:

“When a bomber blows himself up he is not directing the attack towards civilians. On the contrary, the attack is designed to target off-duty soldiers (which I was told did not mean reservists, since most Israelis are technically reservists). The innocent civilians are unfortunate collateral damage in the targeting of soldiers.”

We say: There are two details here.

Tafsīl A: Off-duty soldiers are treated as civilians.

Our jurists agree that during a valid war when there is no ceasefire, and when an attack is not aimed at a valid military target, a hostile soldier (whether male or female, whether conscripted or not) who is not on operational duty or not wearing a military uniform and when there is nothing in the soldier’s outward appearance to suggest that the soldier is in combat, then the soldier is considered a non-combatant [man lā yuqātilu] (and in this case must therefore be treated as a normal civilian).

A valid military target is limited to either a battlefield [mahall al-ma’raka or sahat al-qitāl] or a military base [mu’askar; medieval examples are citadel or forts; modern examples are barracks, military depots, etc.]; and certainly never can anything else such as a restaurant, a hotel, a public bus, the area around a traffic light, or any other public place be considered a valid military target, since firstly, these are not places and bases from which an attack would normally originate [mahall al-ra’y]; secondly, because there is certain knowledge [yaqīn] that there is intermingling [ikhtilāt] with non-combatants; and thirdly, the non-combatants have not been given the option to leave the place.

As for when the soldiers are on the battlefield, the normal rules of engagement apply.

As for when the soldiers are in a barracks or the like, there is further discussion on whether the soldiers become a legitimate target, and the Qawl Asahh [the More Correct Position] according to our jurists is that they do, albeit to attack them there is makrûh.

Tafsīl B: Non-combatants cannot at all be considered collateral damage except at a valid military target, for which they may be so deemed, depending on certain extenuating circumstances.

There is no khilāf that non-combatants or civilians cannot at all be considered collateral damage at a non-military target in a war zone, and that their deaths are not excusable by our Law, and that the one who ends up killing one of them will be sinful as in the case of murder, even though the soldier who is found guilty of it would be excused from the ordinary capital punishment [hadd], unless the killing was found to be premeditated and deliberate:

|

"aw ata bi-ma’siyyatin tujibu l-hadda"

|

If not, the murderer’s punishment in this case would instead be subject to the authority’s discretion [ta’zīr] and he would in any case be liable to pay the relevant compensation [diya].

As for a valid military target in a war zone, the Shāfi’ī School have historically considered the possibility of collateral damage, unlike the position held by others that it is unqualifiedly outlawed. The following are the conditions stipulated for allowing this controversial exception (in addition to meeting the most important condition of them all: that this takes place during a valid war when there is no ceasefire:)

- The target is a valid military target.

- The attack is as a last resort [min darura] (such as when civilians have been warned to leave the place and after a period of siege has elapsed):

"wujub al-indhari qabla l-bad’i bi-l-qatli li-annahu la yajuzu an yaqtula illa man yuqatilu" - There are no Muslim civilians or prisoners.

- The decision to attack the target is based on a considered judgement of the executive or military leader that by doing so, there is a good chance that the battle would be won.

(Furthermore, this position is subject to khilāf among our jurists with regard to whether the military target can be a Jewish or Christian [Ahl al-Kitāb] one, since the sole primary text that is invoked to allow this exception concerns an incident restricted to the same “mushrikin” as in the Verse of Surah al-Tawbah in Question II above.)

This is why the means of an act [‘amal] must be correct and validated according to the rule of Law in order for its outcome to be sound and accepted, as expressed succinctly in the following wisdom of Imam Ibn ‘Ata’illah (may Allāh sanctify his soul):

|

| "man ashraqat bidayatuhu ashraqat nihayatuhu" |

[He who makes good his beginning will make good his ending.]

| "wasilatu t-ta’ati ta’atun wa-wasilatu l-ma’siyati ma’siyatun" |

[the means to a reward is itself a reward and the means to a sin is itself a sin.]

Wallāhu a’lam wa-ahkam bi-s-sawab! [God knows and judges best what is right!]

Question V

If it is said:

“In a classic manual of Islamic Sacred Law ["Reliance of the Traveller"] I read that “it is offensive to conduct a military expedition [ghazw] against hostile non-Muslims without the caliph’s permission (though if there is no caliph, no permission is required).” Doesn’t this entail that though it is makrûh for anyone else to call for or initiate such a jihād, it is permissible?”

We say:

|

| "la ghazwata illa fi l-jihadi" |

[There is no battle except during a war.]

The context is that of endangering one’s life [taghrīr bi-nafs] when there is already a valid war with no ceasefire, as seen in the above example from the Ihyā’ passage, but certainly not in executive matters of the kind of proclaiming a war and the like. This is also obvious from the terminology used: a ghazw [a military act, assault, foray or raid; the minimum limit in a modern example: an attack by a squad or a platoon (katība) ] can take place only when there is a state of jihād [war], not otherwise.

Fā’ida: Imām Ibn Hajar (may Allāh be pleased with him) lists the organizational structure of an army as follows:

- a ba’th [unit] and several such together, a katība [platoon],

- which is a part of a sariyya [company; made up of 50-100 soldiers],

- which is in turn a part of a mansar [regiment; up to 800 soldiers],

- which is a part of a jaysh [division; up to 4000 soldiers],

- which is a part of a jahfal [army corps; exceeding 4000 soldiers],

- which makes up the jaysh ‘azīm [army].

In our School, it is offensive but not completely prohibited for a soldier to defy, or in other words to take the initiative against the wishes of, his direct authority, whether his unit is strong or otherwise. In the modern context, this may include cases when soldier(s) disagree with a particular decision or strategy adopted by their superior officers, whether during a battle or otherwise.

The accompanying commentary to the text you quoted will help clarify this for you:

[Original Text:] It is offensive to conduct an assault [whether the unit is strong (man’a) or otherwise; and some have defined a strong force as 10 men] without the permission of the authority. ([Commentary:] or his subordinate, because the assault depends on the needs [of the battle and the like] and the authority is more aware about them. It is not prohibited [to go without his permission] (if) there is no grave endangering of one’s life even when that is permissible in war.)

Source: [Ibn Barakat, Fayd, 2:309]

Question VI

If it is said:

“What is the meaning of the rule in fiqh that I always hear, that jihād is a fard kifāya [communal obligation] and when the Dār al-Islām is invaded or occupied it is a fard ‘ayn [personal obligation]? How do we apply this in the context of a modern Muslim state such as Egypt?”We say:

It is fard kifāya for the eligible Muslim subjects of the state in the sense that recruitment to the military is only voluntary when the state declares war with a non-Muslim state (as for non-Muslim subjects, they evidently are not religiously obligated but can still serve). It becomes a fard ‘ayn for any able-bodied Muslim when there is a conscription or a nationwide draft to the military if the state is invaded by a hostile non-Muslim force, but only until the hostile force is repelled or the Muslim authority calls for a ceasefire. As for those not in the military, they have the option to defend themselves if attacked even if they have to resort to throwing stones and using sticks.

|

| "bi ayyi shay’in ataquhu wa-law bi-hijaratin aw ‘asa" |

When it is not possible to prepare for war [and rally the army for war (ijtimā’ li-harb), and a surprise attack by a hostile force completely defeats the army of the state and the entire state becomes occupied] and someone [at home, for example] is faced with the choice of whether to surrender or to fight [such as when the hostile force comes knocking at the door], then he may fight.

Or he may surrender, provided that he knows [with certainty] that if he resisted [arrest] he would be killed and that [his] wife would be safe from being raped [fāhisha] if she were taken. If not [that is to say, even if he surrenders he knows he will be killed and his wife raped when taken], then [as a last resort] fighting [jihād] becomes personally obligatory for him.

Source: [al-Bakri, I’ānat, 4:197]

Reflect upon this legal ruling of our Religion and the emphasis placed upon preserving human life and upon the wisdom of resorting to violence only when it is absolutely necessary and in its proper place; and witness the conjunction between the maqāsid and the wasā’il and the meaning of the conditions when fighting actually becomes a fard ‘ayn for an individual!

Question VII

If it is said today:

“In the [Shafi`i] Madhhab, what are the different classifications of lands in the world? For example, Dar al-Islam, Dar al-Kufr and so forth, and what have the classical ulema said their attributes are?”We say:

As it is also from empirical fact [tajrība], Muslim scholars have classified the territories in this world into: Dār al-Islām [its synonyms: Bilād al-Islām or Dawla al-Islām; a Muslim state or territory or land or country, etc.] and Dār al-Kufr [a non-Muslim state, territory etc.]

The definition of a Muslim state is:

“any place at which a resident Muslim is capable of defending himself against hostile forces [harbiyyûn] for a period of time is a Muslim state, where his judgements can be applied at that time and those times following it.”

Source: [Ba’alawi, Bughya, 254]

A non-Muslim who resides in a Muslim state is, in our terminology: kāfir dhimmi or al-kāfir bi-dhimmati l-Muslim [a non-Muslim in the care of a Muslim state].

By definition, an area is a Muslim state as long as Muslims continue to live there and the political and executive authority is Muslim.

As for a non-Muslim state, it is the absence of a Muslim state.

As for the Dār al-Harb [sometimes called, Ard al-‘Adw ], it is a non-Muslim state which is in a state of war with a Muslim state. Therefore, a hostile non-Muslim soldier from there is known in our books as: kāfir harbī.

Furu’: Even if such a person enters or resides in a Muslim country that is in a state of war with his home country, provided of course he does so with the permission of the Muslim authority (such as entering with a valid visa and the like), the sanctity of a kāfir harbī’s life is protected by Law, just like the rest of the Muslim and non-Muslim subjects of the state. [al-Kurdi, Fatāwā, 211-2]. In this case, his legal status becomes a kāfir harbī bi-dhimmati l-imām [a hostile non-Muslim under the protection of the Muslim authority], and for all intents and purposes, he becomes exactly like the non-Muslim subjects of the state. In this way, the apparent difference between a dhimmī and a harbī non-Muslim becomes only an academic exercise and a distinction in name only.

The implications of this rule for the pious, God-fearing and Law-abiding Muslims are not only that to attack non-Muslims becomes something illegal and an act of disobedience [ma’siya], but also that the steps taken by the Muslim authority and enforcers, such as in Malaysia or Indonesia today, to protect their places, including churches or temples, from the threat of killings and bombings, are included under the bāb of amr bi-ma’ruf wa nahi ‘ani l-munkar [the duty to intervene when another is acting wrongly; in the modern context: enforcing the Law], even if the Muslim enforcers [muhtasib] die in the course of protecting non-Muslims.

Question VIII

We say: It is clear that the countries in the Union are non-Muslim states, except for Turkey, for example, if they are a part of the Union. The status of the Muslims who reside and are born in non-Muslim states is the reverse of the above non-Muslim status in a Muslim state: al-Muslim bi-dhimmati l-kāfir [a Muslim in the care of a non-Muslim state] and from our own Muslim and religious perspective, whether we like it or not, there are similarities to the status of a guest which should not be forgotten.

There is precedent for this status in our Law. The answer to your question is that they should as a practical matter remain in these countries, and if applicable, learn to cure the schizophrenic cultural condition in which they may find themselves – whether of torn identity in their souls or of dissociation from the general society. If they cannot do so, but find instead that their surroundings are incompatible with the life they feel they must lead, then it is recommended for them to leave and reside in a Muslim state. This status is made clear in the fatwa of the Muhaqqiq, Imam al-Kurdi (d. 577 AH/1181 CE - may Allāh be pleased with him!). He was asked:

Question: In a territory ruled by non-Muslims, they have left the Muslims [in peace] other than that they pay tax [māl] every year just like the jizya-tax in reverse, for when the Muslims pay them, their protection is ensured and the non-Muslims do not oppose them [i.e., do not interfere with them]. Thereupon, Islam becomes practiced openly and our Law is established [meaning that they have the freedom to practice their religious duty in the open and in effect become practicing Muslims in that non-Muslim society]. If the Muslims do not pay them, the non-Muslims could massacre them by killing or pillage. Is it permissible to pay them the tax [and thereby become residents there]? If you say it is permissible, what is the ruling about the non-Muslims mentioned above when they are at war [with a Muslim state]: would it or would it not be permissible to oppose them and if possible, take their money? Please give us your opinion!

His answer: Insofar as it is possible for Muslims to practice their religion openly with what they can have power over, and they are not afraid of any threat [fitnah] to their religion if they pay tax to the non-Muslims, it is permissible for them to reside there. It is also permissible to pay them the tax as a requirement of it [residence]; rather, it is obligatory [wājib] to pay them the tax for fear of their causing harm to the Muslims. The ruling about the non-Muslims at war as mentioned above, because they protect the Muslims [in their territory], is that it would not be permissible for the Muslims to murder them or to steal from them.

Source: [al-Kurdi, Fatawa, 208]

The dābit for this mas’ala is:

|

| "wa-in qadara ‘ala izhari d-dini wa-lam yakhafi l-fitnata fi d-dini wa-nafsihi wa-malihi lam tajib ‘alayhi al-hijratu" |

[If someone is able to practice his religion openly and is not afraid of trouble to his religion, life and property, then emigration is not obligatory for him.]

- Harām: It is prohibited for them to leave when they are able to defend their territory from a hostile non-Muslim force or withdraw from it (as in the case of a border state, buffer area or disputed territory) and do not need to ask for help from a Muslim state. The reason is that their place of residence is already, technically [hukman], a ‘Muslim state’ even though not in name [sûratan], since they are able to practice their religion openly even though the political or executive authority is not Muslim; and if they emigrated it would cease to be so. This falls under the fiqhī classification of Dār Kufr Sûratan Lā Hukman, which is equivalent to Dār Islām Hukman Lā Sûratan.

- Makrûh: it is offensive to leave their place of residence when it is possible for them to practice their religion openly, and they wish to do so openly.

- Mandûb: leaving becomes recommended only when it is possible for them to practice their religion openly, but they do not wish to do so.

- Wājib: it becomes obligatory to leave when it is the only remaining option, that is, when practicing their religion openly is not possible. A legal precedent is the case after the Reconquista in Spain (which is no longer the case today) when the Five Pillars of the Faith were actively proscribed, so that, for example, the Muslim houses were required to keep their doors open after sunset during the fasting month of Ramadān in order that the authority could see that there was no breaking of the fast.

Question IX

“Would you say that in the modern age with all the considerations surrounding sovereignty and inter-connectedness, these classical labels do not apply any longer, or do we have sufficient resources in the School to continue using these same labels?”We say: As Imam al-Ghazālī used to say:

|

| "idhā `urifa l-ma`nā falā mushāhhata fī l-asmāmī" |

[Once the real meaning is understood, there is no need to quibble over names.]

Labels can never be relied upon; it is the meaning behind them that must be properly understood. Once they are unpacked, they immediately become relevant for all times; just as with the following loaded terms: jihād, mujāhid and shahīd. The result for Muslims who fail to notice the relevance and fail to connect the dots of our own inherited medieval terms with the modern world may be that they will live in a schizophrenic cultural reality and will be unable to associate themselves with the surrounding society and will not be at peace [sukûn] with the rest of creation. Just as the sabab al-wujûd of this article is a Muslim’s misunderstanding of his own medieval terminology from a long and rich legacy, the fitnah in the world today has been the result of those who misunderstand our Law.

Pay heed to the words of Mawlānā Rûmī (may Allāh sanctify his secrets):

Go beyond names and look at the qualities, so that they may show you the way to the essence.

The disagreement of people takes place because of names. Peace occurs when they go to the real meaning.

Every war and every conflict between human beings has happened because of some disagreement about names.

It is such an unnecessary foolishness, because just beyond the arguing there is a long table of companionship, set and waiting for us to sit down.

End of the masā’il section.

Tatimma

It is truly sad that despite our sophisticated and elaborate set of rules of engagement and in spite of the strict codes of warfare and the chivalrous disciplines which our soldiers are expected to observe, all having been thoroughly worked out and codified by the orthodox jurists of the Ummah from among the generations of the Salaf, there are today in our midst those who are not ashamed to depart from these sacred conventions in favour of opinions espoused by persons who are not even trained in the Sacred Law at all let alone enough to be a qādī or a faqīh – the rightful heir and source from which they should receive practical guidance in the first place. Instead they rely on engineers or scientists and on those who are not among its ahl, yet speak in the name of our Law. With these “reformist” preachers and da’īs comes a departure from the traditional ideas about the rules of siyar/jihād/qitāl, i.e., warfare.

Do they not realize that by doing so and by following them they will be ignoring the limitations and restrictions cherished and protected by our pious forefathers and that they will be turning their backs on the Jamā’a and Ijmā’ and that they will be engaging in an act for which there is no accepted legal precedent within orthodoxy in our entire history? Have they forgotten that part of the original maqsad of warfare/jihād was to limit warfare itself and that warfare for Muslims is not total war, so that women, children and innocent bystanders are not to be killed and property not to be needlessly destroyed?

To put it plainly, there is simply no legal precedent in the history of Sunni Islam for the tactic of attacking civilians and overtly non-military targets. Yet the awful reality today is that a minority of Sunni Muslims, whether in Iraq or Beslan or elsewhere, have perpetrated such acts in the name of jihād and on behalf of the Ummah. Perhaps the first such mission to break this long and admirable precedent was the bombing of a public bus in Jerusalem in 1994 – not that long ago. (Reflect on this!)

Immediately after the incident, the almost unanimous response of the orthodox Shāfi’ī jurists from the Far East and the Hadramawt was not only to make clear that the minimum legal position from our Sacred Law is untenable for persons who carry out such acts, but also to warn the Ummah that by going down that path we would be compromising the optimum way of Ihsān and that we would thereby be running a real risk of losing the moral and religious high ground. Those who still defend this tactic, invoking blindly a nebulous usûlī principle that it is justifiable out of darûra while ignoring the far’ī strictures, must look long and hard at what they are doing and ask the question: was it absolutely necessary, and if so, why was this not done before 1994, and especially during the earlier wars, most of all during the disasters of 1948 and 1967?

How could such a tactic be condoned by one of our Rightly Guided Caliphs and a heroic fighter such as ‘Alī (may Allāh ennoble his face!), who when in the Battle of the Trench his notorious non-Muslim opponent, who was seconds away from being killed by him, spat on his noble face, immediately left him alone. When asked later his reasons for withdrawing when Allāh clearly gave him power over him, he answered: “I was fighting for the sake of God, and when he spat in my face I feared that if I killed him it would have been out of revenge and spite!” Far from being an act of cowardice, this characterizes Muslim chivalry: fighting, yet not out of anger.

In actual fact, the only precedent for this tactic from Muslim history is the cowardly terrorism carried out by the “Assassins” of the Nizari Isma’īlīs. Their most famous victim from a suicide mission was the wise minister and the Defender of the Faith, who could have been alive to deal with the fitna of the Crusades: Nizām al-Mulk, the Jamāl al-Shuhadā’ (may Allāh encompass him with His mercy!), assasinated on Thursday, the 10th of the holy month of Ramadan 485 AH/14 October 1092 CE.

Ironically, in the case of Palestine, the precedent was set not by Muslims but by early Zionist terrorist gangs such as the Irgun, who, for example, infamously bombed the King David Hotel in Jerusalem on 22nd July 1946. So ask yourself as an upright and God-fearing believer, whose every organ will be interrogated: do you really want to follow the footsteps and the models of those Zionists and the heterodox Isma’īlīs, instead of the path taken by our Beloved (may Allāh’s blessings and peace be upon him!), who for almost half of the (twenty-three) years of his mission endured Meccan persecution, humiliation and insults? Is anger your only strength? If so, remember the Prophetic advice that it is from the Devil. And is darûra your only excuse for following them instead into their condemned lizard-holes? Do you think that any of our famous mujāhids from history, such as ‘Ali, Salāh al-Dīn, and Muhammad al-Fātih (may Allāh be well pleased with them all!) will ever condone the article you quoted and these acts today in Baghdad, Jerusalem, Cairo, Bali, Casablanca, Beslan, Madrid, London and New York, some of them committed on days when it is traditionally forbidden by our Law to fight: Dhû l-Qa’da and al-Hijja, Muharram and Rajab? Every person of fitra will see that this is nothing other than a sunnah of perversion.

This is what happens to the Banû Adam when the wahm is abandoned by ‘aql, when one of the maqāsid justifies any wasīla, when the realities of furû’ are indiscriminately overruled by generalities of usûl, and most tragically, as illustrated from the eternal blunder of Iblis, when Divine tawakkul is replaced by basic nafs.

Yes, we are one Ummah such that when one part of the macro-body is attacked somewhere, another part inevitably feels the pain. Yet at the same time, our own history has shown that we have also been a wise and sensible, instead of a reactive and impulsive, Ummah. That is the secret of our success, and that is where our strengths will always lie as has been promised by Divine Writ: in sabr and in tawakkul. It is already common knowledge that when Jerusalem fell to the Crusading forces on the 15th of July 1099 CE and was occupied by them, and despite its civilians having been raped, killed, tortured and plundered and the Umma at the time humiliated and insulted – acts far worse than what can be imagined in today’s occupation – that it took more than 100 years of patience and legitimate struggle under the Eye of the Almighty before He allowed Salāh al-Din to liberate Jerusalem. We should have been taught from childhood by our fathers and mothers about the need to prioritize and about how to reconcile the spheres of our global concerns with those of our local responsibilities – as we will definitely not escape the questioning in the grave about the latter – so that by this insight we may hope that our response will not be disproportionate nor inappropriate. This is the true meaning [haqīqa] of the true advice [nasīha] of our Beloved Prophet ﷺ: to leave what does not concern one [tark ma lā ya’nīh], where one’s time and energy could be better spent in improving the lot of the Muslims today or benefiting others in this world.

Yes, we will naturally feel the pain when any of our brothers and sisters die unjustly anywhere when their deaths have been caused directly by non-Muslims, but it must be just as painful for us when they die in Iraq, for example, when their deaths are caused directly by the self-destroying/martyrdom/suicide missions carried out by one of our own. On tafakkur, the second pain should make us realize that missions of this sort, when the means and the legal particulars are all wrong – by scripture and reason – are a plague and great fitnah for this mercied Ummah, and desire insāf so that out of maslaha and the general good, it must be stopped.

To this end, we could sum up a point of law tersely in the following maxim:

|

| "la yaj’alu z-zulmani th-thaniya haqqan" |

[two wrongs do not make the second one right]

My brethren, when the military option is not a legal one for the individuals concerned, you must not lose hope in Allāh; and let us be reminded of the words of our Beloved ﷺ:

|

| "afdalu l-jihadi kalimatu haqqin ‘inda sultanin ja’irin" |

[The best jihad is a true (i.e., brave) word in the face of a tyrannical ruler.]

(From a Hadīth of Abû Sa’īd al-Khudrī (may Allāh be well pleased with him!) among others, which is related by Ibn al-Ja’d, Ahmad, Ibn Humayd, Ibn Mājāh, Abû Dawûd, al-Tirmidhī, al-Nasā’ī, Abû Ya’lā, Abû Bakr al-Rûyānī, al-Tabarānī, al-Hākim, and al-Bayhaqī, with variants.)

For it is possible still, and especially today, to fight injustice or zulm and taghût in this dunyā through your tongue and your words and through the pen and the courts, which still amounts in the Prophetic idiom to jihād, even if not through war. As in the reminder [tadhkira] of the great scholar, Imām al-Zarkashī: war is only a means to an end and as long as some other way is open to us, that other way should be the course trod upon by Muslims.

With this intention, we may hope that we shall regain our former high ground and reputation and rediscover our honour and chivalrous qualities and be no less brave.

May this be of benefit.

With heartfelt wishes for salām & tayyiba

from Oxford to Brunei,

Muhammad Afifi al-Akiti

16th Jumādā’ II 1426 AH

23rd July 2005 CE