The Kalām Cosmological Argument and Atomism

Introduction

Perhaps the most well-known form of the Kalam cosmological argument is that as propagated by William Lane Craig. Yet, in his attempt to introduce it to the Western philosophical tradition, he has stripped the 'kalām' from the argument; rendering it a shallow husk.

The Kalam cosmological argument is so-called as its formation lies in the Muslim kalām tradition. Originating in the study circles of Basra in the 8th century CE and influenced by the texts of Aristotle, kalām (lit. 'speech') is a form of Islamic discursive theology initially formed to rationally defend Sunni orthodoxy and refute heterodox groups such as the Muʿtazilah (rationalists). The development of kalām paved way for the formation of two of the three Islamic schools of theology (the Ashʿarīs and Māturīdis), and the development of a novel atomic theory - the cornerstone of the Kalam cosmological argument.

Brief primer on Kalam atomism

- qadim – eternal, timeless;

- or it is hadith – contingent, coming into existence (wujud) after non-existence (‘adm).

To put it another way: Every entity that exists, either exists by itself; by its own essence and nature, or it does not exist by itself. If it exists by its own essence, then it exists necessarily and eternally, and explains itself. It cannot not exist. But if an entity exists, but not by its own essence, then it needs a cause outside of itself for its existence.

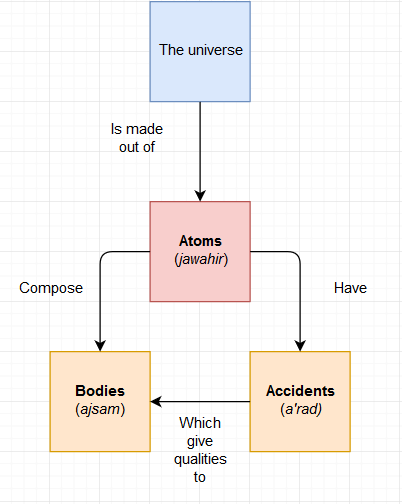

Next, we move onto 'atomism' in one of the foundations of kalām theology. It can be summarised as follows:

The universe is made out of:

- 'atoms' (jawahir, sing. jawhar),

- bodies (ajsam, sing. jism)

- and accidents (a‘rad, sing. ‘arad)

The kalām 'atom' (jawhar) must not be confused with the concept of an atom in modern science. Rather, it is defined as a particle which:

- is indivisible and occupies space (tatahayyaz)

- is subject to change (taghayyur)

- has no innate power of duration (thubut, baqa') but endures directly because of God through each moment of its existence.

A body (jism) is therefore composed of atoms that occupy space. It is described of in terms of height, length and depth. Anything that occupies space and has a position is a jism.

An accident (a‘rad) occurs because of an extraneous cause and cannot exist by itself, instead inhering in atoms. Colour is an example of an accident.

It is important to note that it is not just the atom which is indivisible. Time itself, in kalām atomism, only comes in finite units: it also having no intrinsic ability to endure. It is God’s continuous act of creating these discrete units of time that allows it to actually “flow.”

The purpose of kalām atomism is to show that everything is hawadith (contingent) and finite. It denies, at each point in the duration of anything non-divine, that it has any intrinsic power of existence. God alone has such a power.

The Kalam cosmological argument

This ties into the kalām cosmological argument via this preamble:

- An actual infinite number does not exist. Everything is finite.

- Therefore, the series of causes for the cosmos to be as it is now cannot be infinite in sequence: that is, it must also be finite;

- Therefore, the cosmos was brought into existence at some point in the past.

This leads to the crux of the argument:

- Everything that begins to exist has a cause.

- The universe that began to exist.

- Therefore, the universe has a cause.

- (The implicit fourth cause is that this something is ultimately God)

Objections to the first premise

"It is wrong to say that 'everything that begins to exist has a cause' because quantum physics appears to show that electrons can pass out of existence at one place and re-appear elsewhere for no apparent reason."

One reply to this states that although electrons do just that, they can only do so because of what is called a “quantum vacuum.” A vacuum, in quantum physics, isn’t “nothing at all”. It is a state of minimal energy, seething with “virtual particles.” It is this vacuum which gives rise to electron fluctuations, says the laws of quantum physics. Which is to say, the vacuum’s existence is the cause for electrons to exist, disappear and re-appear, and these electrons are hawadith.

The premise states: "Everything that begins to exist has a cause." However, God did not begin to exist. This is because conventional notions of time and space simply do not apply to Him as they are His creation; Islamic theologians have stressed He is the musabib al-asbab (the [uncaused] Causer of all things). To quote Aqeedah al-Tahawiyyah, "He is pre-existent without beginning, eternal without ending". God cannot have a cause, therefore He necessarily exists (wajib al-wujud)."If everything has a cause, what caused God?"

In Islamic theology it is said that He exists in pre-eternity and is timeless. Pre-eternity does not mean before the beginning of the time. Rather, in pre-eternity, there is no past, present and future. So because God is timeless, eternal and did not come into existence after non-existence, He is therefore qadim and everything else (i.e. the creation) that is hadith. As mentioned earlier, all that comes into existence, after not existing (something that is hadith), must have a cause for its existence - but this does not apply to God, who is qadim.

"We do not know whether or not something can begin to exist without a cause."

Let's say an object begins to exist. It comes into existence after non existence; it is hadith. In kalām theology, a proposition is either:

- Necessary (wajib) → so it is true or false

- Possible (mumkin, i.e. contingent or conceivable) → so they are affirmations or negations

- Impossible (muhaal)

Let's consider the proposition "An object began to exist without a cause."

The possibility that this event is muhaal will be initially dismissed, because it will be assumed that the event actually took place and that the object began to exist. That leaves us with two options to consider.

If this was wajib, then what can be said about the object's necessity for emerging is that it is either:

- Intrinsic to the object

- Extrinsic to the object

There is no third alternative. The first possibility can be dismissed because the object was at first non-existent. That which is non-existent cannot bring itself into existence, because in order for it to perform such an action, it would have to exist. But because it doesn't exist in the first place, it can never bring itself into existence. The object's necessity of emerging must therefore be extrinsic to the object. Therefore, it has a cause.

If this was mumkin, and not wajib, then this means that the object emerging could have occured, or it could have remained non-existent. The emergence of the object therefore must have overrode its former non-existing state. Therefore, what can be said about this overriding is that it is either:

- Intrinsic to the object

- Extrinsic to the object

We can dismiss the first possibility because the object was at first non-existent, and what does not exist can not be said to have any will or influence on anything. It could therefore not have chosen to create itself. Again, we're left with the second option, which is that the outweighing of the two options (emerging or remaining non-existent) must be extrinsic to the object. Therefore, it has a cause.

Objections to the second premise

"The universe did not begin to exist. It is possible it has existed for an infinitely long period of time."The claim "The universe began to exist" is:

- straightforward

- intuitive

- a simple generalisation of our everyday experience. Everything we experience in the universe has an age; that is to say, it has existed for a finite period of time and began to exist. If everything we experience in the universe has an age and began to exist, it is perfectly reasonable to claim that the universe as a whole too must have an age and must have begun to exist. We have never seen anything to the contrary; that is, something that has existed forever within the universe.

The opposing claim "The universe did not begin to exist. It is possible for the universe to have existed for an infinitely long period of time" is therefore:

- strange

- counter-intuitive

- unreasonable as it is contrary to our experience

- This is logically equivalent to the claim "The universe has existed for an infinite period of time."

- This, in turn, is logically equivalent to the claim "An infinite quantity of time has elapsed in the universe".

- This is because the claim "the universe has existed for an infinite quantity of time" is to say that there is an endless quantity of time in the backwards direction - but it has nevertheless reached the present moment. That is to say that "An infinite quantity of time has elapsed."

Because these three claims are logically equivalent, if one of them is false, then the other two claims are false.

We can see the claim "An infinite quantity of time has elapsed." is false upon further reflection.

- The adjective 'infinite' means endless.

- The present perfect tense verb "has elapsed" means "has come to an end."

Miscellaneous objections

Either:

"What if the cause of the universe is two or more omnipotent deities? Why does it have to be one?"This diagrams show the logical impossibility of the existence of more than one omnipotent entity. In the diagram below, there are two omnipotent deities, A and B:

|

- Both wills are effected, so X both exists and doesn't exist simultaneously - which is muhaal

- Only the will of one deity is effected and the will of the other is overcome - meaning the latter is not omnipotent.